Murky ocean impacts from COVID-19 emissions reductions

University of Hawaiʻi at MānoaProfessor, Oceanography, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology

Marcie Grabowski, 808-956-3151

Outreach specialist, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the first half of 2020, the lack of human activity around the world resulted in a 9% drop in the greenhouse gas emissions at the root of climate change.

Almost overnight, the Himalayas became visible from a distance for the first time in years. Rivers flowed free of toxic pollutants and the air sparkled with blue skies in major cities such as New Delhi and Los Angeles. While internet rumors of swans and dolphins returning to Venetian canals were debunked, the idea that “nature is healing” in 2020 quickly took root.

Unfortunately, any silver lining from the pandemic remains murky in the oceans.

At the American Geophysical Union 2020 Fall Meeting, a team of scientists, including Christopher Sabine, oceanography professor at the University of Hawai‘i Mānoa, shared the results of their research that showed no detectable slowing of ocean acidification due to COVID-19 emissions reductions. Even at emissions reductions four times the rate of those in the first half of 2020, the change would be barely noticeable.

“It’s almost impossible to see it in pH,” said Nicole Lovenduski, University of Colorado associate professor and lead author of the study. “So has this solved ocean acidification? No, it has not.”

On the bright side, the researchers now have a better idea of where to look for the signs of impactson the Earth system from emissions reductions, what they will look like and the resources they will need to gather that data.

Lovenduski analyzed data shared by a group of Canadian modelers, who ran a suite of experiments to see how the climate has been impacted by the reduction in emissions in 2020. Using a fingerprinting technique on the data often used to differentiate humans’ impacts on the climate from non-human impacts such as volcanic eruptions, the team separated COVID-19 emissions reductions from non-human influences on the oceans.

While they found no perceptible change in ocean acidity, their analysis showed that by 2021, the oceans will be absorbing slightly less carbon from the atmosphere due to COVID-19 emissions reductions.

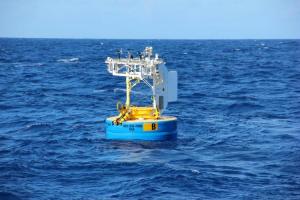

Though it is too soon to measure ocean changes from the COVID-19 related carbon emissions reductions, there is a network of ocean observatories regularly making the measurements necessary to detect the signal when it does show up.

“We are constantly monitoring the carbon concentrations in the ocean and the atmosphere around Hawaiʻi,” said Sabine. “If emissions continue to drop, we are well positioned to document the positive impact that will have on our ocean chemistry and the health of our coral reefs.”

Studying the COVID-19 signal in the ocean provides a unique opportunity to understand how implementing the emissions reductions called for in the Paris Agreement will benefit our state and the world.